Pietro Aretino (1492–1556) – the father of yellow journalism and literary pornography

Medal with the image of Pietro Aretino, pic. Wikipedia

Portrait of Pietro Aretino, Titian, Palazzo Pitti, Florence, pic. Wikipedia

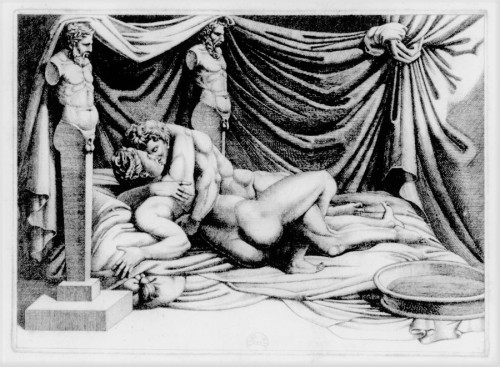

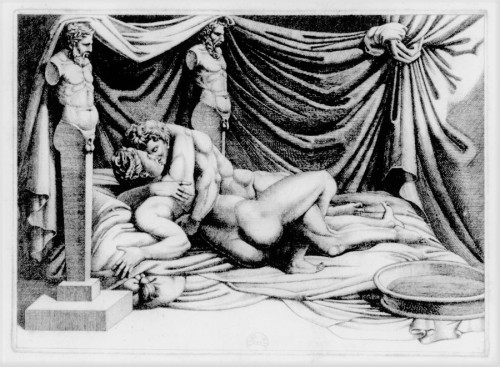

I Modi, engravings enriched with sonnets by Pietro Aretino, Marcantonio Raimondi, pic. Wikipedia

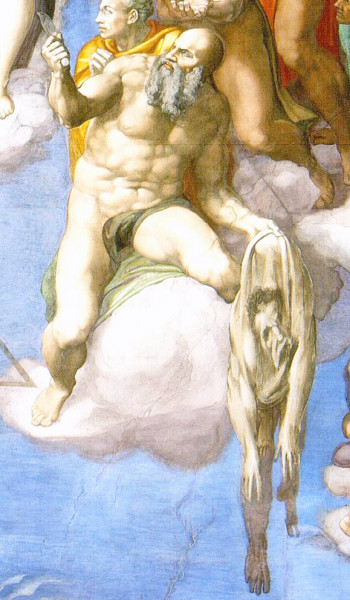

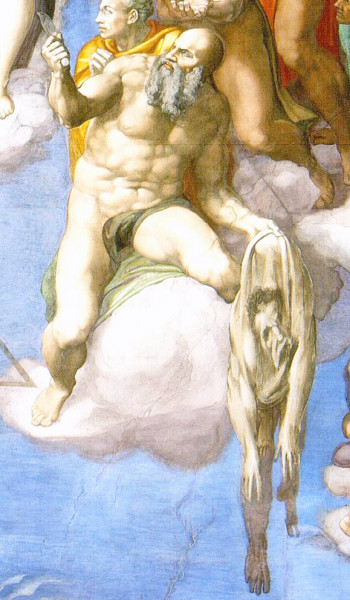

The Last Judgment, Michelangelo, Aretino as St. Bartholomew, Sistine Chapel, Apostolic Palace, pic. Wikipedia

The Last Judgment, Michelangelo, Sistine Chapel, Apostolic Palace pic. Wikipedia

Portrait of Pietro Aretino, Titian, Palazzo Pitti, Florence, pic. Wikipedia

Portrait of Pietro Aretino, fragment, Titian, Palazzo Pitti, Florence, pic. Wikipedia

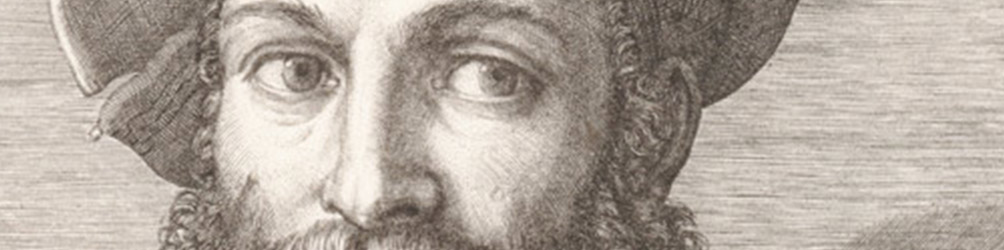

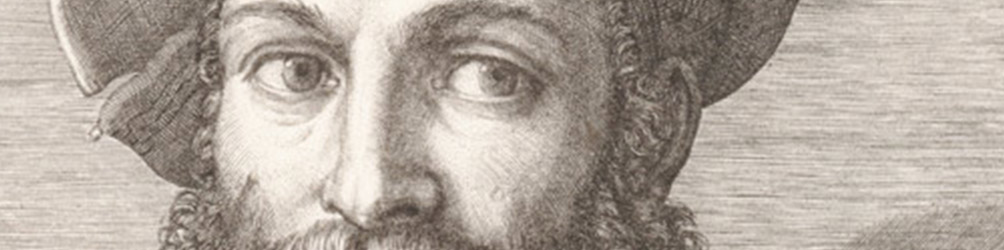

Portrait of Pietro Aretino, Marcantonio Raimondi, pic. Wikipedia

Portrait of Pietro Aretino, Titian, The Frick Collection, New York, pic. Wikipedia

Portrait of Pietro Aretino, fragment, Titian, The Frick Collection, New York, pic. Wikipedia

The death of Pietro Aretino, Anselm Feuerbach, 1854, Art Museum, Basel, pic. Wikipedia

The image of the Italian Renaissance, but also Rome of that time, would not be complete without him – a writer of great ability, an art expert, an inquisitive observer of the surrounding reality, but also an extraordinary slanderer and taunter. He referred to himself as "a free man by God's grace". He claimed to be independent in his judgments since he served no one, but he forgot to mention that the price of this freedom was either praise or slander, which he used willingly for material gain. His calumnies, gossips, and insults were feared by all, including emperors, kings, and popes. Aretino's words could ruin a life, reputation, or career. His silence was a hot commodity indeed.

The image of the Italian Renaissance, but also Rome of that time, would not be complete without him – a writer of great ability, an art expert, an inquisitive observer of the surrounding reality, but also an extraordinary slanderer and taunter. He referred to himself as "a free man by God's grace". He claimed to be independent in his judgments since he served no one, but he forgot to mention that the price of this freedom was either praise or slander, which he used willingly for material gain. His calumnies, gossips, and insults were feared by all, including emperors, kings, and popes. Aretino's words could ruin a life, reputation, or career. His silence was a hot commodity indeed.

He visited Rome several times, always searching for commissions, patrons, and opportunities to earn money. That should come as no surprise. He was born in Arezzo (hence the nickname Aretino), in a poor family, and only thanks to his intelligence and talents, first of all, his painting ability, then literary, he gradually ascended the rungs of the career ladder. He first came to the city on the Tiber, as a twenty-five-year-old in 1517, and immediately was caught in the middle of a true artistic fervor, where the main role was played by Raphael and the artists gathered around him (Giulio Romano, Sodoma, Peruzzi). The banker, Agostino Chigi, who was an enthusiast of both art and the pleasures of daily life, helped young Pietro, who not only had a great sense of humor but also exhibited a satirical gift, in finding a job. He could do no better, as he soon found himself at the court of Cardinal Giulio Medici – the future Pope Clement VII. The nightly feasts at Chigi’s home, or with one of the Roman courtesans, intellectual meetings with the greatest writers (cardinals Bembo and Bibbiena, Ariosto), the never-ending feasts and hunts at the court of Pope Leo X had to leave their mark on Aretino. He became familiar with both the world of Church dignitaries and the community of the Roman courtesans, but also that of cheap prostitutes and their clients.

He quickly saw that his main weapon and greatest asset was slander and satire – a weapon which aroused fear and respect in even the most powerful.

After the death of Leo X, for over a year and a half, the papal throne was occupied by the aesthetic Hadrian VI. Aretino wrote texts which ridiculed the pontiff (pasquinate), that were placed on the statue of Pasquino, which had for years served as an outlet for satire directed at the wealthy of the world. However, quite soon along with his patron cardinal Medici, Aretino left the city ruled by the severe pope and returned in 1523 when Clement VII began his pontificate. At the time he was already well-known and knew the ins and outs of the papal court. He willingly participated in the courtly intrigues until finally, his crude tongue came face to face with a real dagger. The man who reached for the weapon was Achille dell Volta – a nobleman of the influential papal secretary Gianmatteo Ghiberti. Reportedly the reason for the stab wounds on the writer's body was a satire portraying the aforementioned secretary as a man in love with his own cook. However, this was only the beginning of Aretino's problems. In Mantua, to which he fled, he wrote a series of sonnets (22 Sonnets of Lust, 1525), which were a sort of literary commentary on the obscene copperplates created according to the drawings of the most famous student of Raphael, Giulio Romano. The engravings appalled the pope's court to such an extent that their author was thrown into a dungeon, while Aretino could no longer count on the support of the bishop of Rome. Feeling insulted and angry, he left the city on the Tiber, but he never "left it alone". Since then, he ceaselessly attacked the pope's court and ridiculed Clement VII. Yet it must be added that Aretino was a very religious man, he wrote the religious text and confessed on a weekly basis.

After departing Rome, he quickly fell into the good graces of the Venetian doge and it is in the city on the Lagoon that he spent the rest of his happy and wealthy life, filled with feasts and discussions on literature in the company of Titian and Jacopo Sansovino, and the adoring Venetian courtesans. He was made yet more famous by letters which he enthusiastically wrote to just about anyone who had anything to say. They were not so much an intimate form of correspondence but more a public statement; they were printed and disseminated. Those written by Aretino were known for their sharp tongue and ruthless slander. Unfortunately, it must be admitted that Aretino used all means at his disposal to acquire fame, even if it meant destroying his adversary. His letter to Michelangelo can serve as an example, as it shows us just how dangerous of an opponent the writer truly was when somebody did not agree to play by his rules. It must be added, that Aretino was an expert and valued art critic, but also a collector. Upon hearing the news that Michelangelo began working on The Last Judgement he immediately declared his willingness to help. He wanted to become the ideological creator of this important work. However, when the painter in a polite but decisive way rejected his attempts, Aretino’s revenge was terrible. The artist, which had until then been praised by him and to whom he previously wrote that "I should show you respect as the world has many kings but only one Michelangelo", became his bitter enemy. He mercilessly attacked his work accusing it of immorality and an unchristian message. He, an author of works bordering on pornography, stigmatized Michelangelo for his immorality, suggesting that the artist maintained sexual relations with men (Tommaso Cavalieri), although Aretino himself boasted about such relations. He accused the ingenious artist of embezzlement and finally ridiculed his works. Michelangelo answered Aretino's attacks in the only way he could. In the center of the altar, there is a figure of St. Bartholomew with the visage of Aretino, holding a piece of skin (the attribute of Bartholomew) with an image of Michelangelo himself. There can be no greater evidence of the impact of the slanderous writer – the one who “can flay you alive”.

Aretino’s greatest literary „hit” was the Ragionamenti (1534, 1536) trilogy. It is perhaps not a text which can amaze with the beauty of its language, the plot, or style. It contains a dialogue of two courtesans (The Lives of Courtesans), which is an outstanding source of knowledge about the world of the then-Roman prostitutes. There is of course a reason for Aretino "returning" to Rome and placing his protagonists in the city rather than in Venice – a place which he was more familiar with. In his story, Rome appears as a nest of corruption. The ruses, greed, vileness, and scheming of the courtesans and hookers are described in a blunt, sometimes obscene language There is just as much bile used to describe the clients of these women – the seekers of a moment of pleasure, deprived, brutal, stingy and in addition infected with the so-called “French disease” (meaning syphilis), men from various levels of society, also the clergy.

Aretino denounced the desires and hidden passions of his readers, and at the same time stripped mankind of all appearances of nobility. When he wrote a letter (a satirical poem) to a high-ranking Church dignitary, in which he related his strange sexual aberration, telling of how he fell in love with a cook, transferring his love of boys into a love of girls, he not so much gossiped about himself, but more sanctioned the then habits and weaknesses of human nature. In the comedy Il Marescalo (1534), on the other hand, he described the luck of his protagonist when he discovered that a girl whom he was forced to marry, was in reality a youth dressed up as a woman.

We may ask ourselves, how is it possible, that while practicing such kind of a profession, Aretino was able to provide for himself due to – as he called it – “the sweat of his inkwell”? Well, it seems that providing such scandalous tales was always well-paid, and especially when they were filled with immorality. This only added to the splendor of their creator. Edward Boyé, the author of the Polish translation and the introduction to the Lives of the Courtesans diagnosed it in the following way: "in not serving the wealthy, he always served money", and he aimed high. He praised Pope Clement VII, his initial benefactor until problems befell him (Sacco di Roma). Then he insulted the pontiff. Both Emperor Charles V, as well as the King of France Francis I, tried to take advantage of Aretino's satirical abilities, and for his help, they showed their appreciation by showering him with gifts, posts, titles, as well as patronage. From time to time they paid for calumnies written about their opponents, but also for discretion. Pope Julius III made Aretino a Knight of St. Peter, but the writer’s ambitions were far greater. There was a reason that he wrote poems praising the pope, which for St. Peter’s successor who was widely criticized for his private life, was a great service. Unfortunately, the writer was disappointed when he learned that the post of cardinal which he expected as a form of thanks was not to be granted to him. At that time he probably could not have predicted that the subsequent pope, Paul IV would place his works on the list of forbidden books.

Aretino died in Venice, most likely of a heart attack, but a legend proclaims that he met a rather different end – one that was better suited to his character. During a wine-filled feast, he saw a monkey clumsily walking around in shoes and erupted in a fit of laughter which caused him to fall from his chair and break his neck, which was the direct cause of his death.

If you liked this article, you can help us continue to work by supporting the roma-nonpertutti portal concrete — by sharing newsletters and donating even small amounts. They will help us in our further work.

You can make one-time deposits to your account:

Barbara Kokoska

BIGBPLPW 62 1160 2202 0000 0002 3744 2108

or support on a regular basis with Patonite.pl (lower left corner)

Know that we appreciate it very much and thank You !